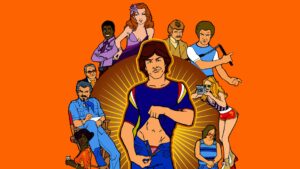

The Penis, The Power, and The Predicaments: An examination of male insecurity and female dehumanization in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights

By: Steve Pulaski

NOTE (ORIGINALLY WRITTEN/PUBLISHED IN 2015: Instead of a conventional review for Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights, I decided to publish an essay I wrote for my college film class discussing the film and its ties to Laura Mulvey‘s theories of phallocentrism, castration, and the male gaze.

Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights adheres to many conventions of gender in terms of the way it portrays women, but subverts its portrayal of men by highlighting masculine insecurity and the fear of being inadequate.

The film concerns a young man named Eddie, played by Mark Wahlberg, who has dropped out of high school and is making ends meet working as a busboy at a nightclub and living with his parents. One day on the job, he catches the eye of Jack Horner (Burt Reynolds), a renowned porn director during the industry’s “Golden Age,” who admires his natural attractiveness and invites him to come spend time with him at his enormous ranch. Numerous people live under Jack’s roof, including a young starlet named “Rollergirl” (Heather Graham), nicknamed because of her obsession with her rollerblades, Maggie (Julianne Moore), an older porn actress famous for a long-running series of films, Buck (Don Cheadle), a struggling stereo salesman, and Reed (John C. Reilly), a squirrely man who seems to just live off of Jack’s dime.

Upon running away from home, Eddie soon becomes “Dirk Diggler,” one of the industry’s most famous and acclaimed porn stars almost overnight; he is glitzed with awards, recognition, and more money than he could ever spend, but slowly allows his masculinity and fragile ego to command him as a person. Such concepts heavily adhere to feminist film writer Laura Mulvey’s ideas of “phallocentrism” and the male gaze. With that, Boogie Nights handles male and female characters quite differently, giving the male characters an inferiority complex that makes them define their worth based on their own personal work, and the two main female characters in the film dichotomous roles, one to showcase attractiveness and the other to showcase the lack thereof.

The pornographic industry has always been under fire for its treatment and sexualized depictions of women. Paul Thomas Anderson immediately dismantles that assertion by giving it some equality; in porn, everyone, regardless of race or gender, is a sex object, though most pay to see said films to have their eyes locked on the females in the film. Consider the fact that in Boogie Nights, Rollergirl, while having a name, which you may have missed, lacks a character. Her mysteriousness is part of her aura and that’s the attraction in porn, Anderson subtly implies. Because we don’t know much about Rollergirl as a character, we, the audience, can appreciate her for her flesh and ability to have sex because we can’t look beneath the surface at her character. Her flat characterization, while devaluing her as a person, essentially makes her successful at what she is trying to convey; an empty vessel capable of great sex many men of varying different ages can only dream about.

Had we learned about Rollergirl as a person – maybe she had a troubled childhood, did poorly in school, or simply doesn’t have a strong and sustainable relationship with her family – she would’ve become less attractive because she would’ve had more baggage, and that’s not the kind of pleasure we pay to see or hear when we watch pornography. Anderson showcases this by portraying Rollergirl as unbridled sexiness as a porn starlet.

Maggie is a different story. Despite her being an older and more popular porn star than Rollergirl, she doesn’t seem as sexy to the audience because we see her personal life. Only in one scene between her and Dirk Diggler do we see her as a sex object; the rest, we see her as a character with real problems. We see her dirty laundry, such as her inability to maintain a stable relationship and her failure to get custody of her young child. Because of Anderson’s choice to humanize Maggie and dehumanize Rollergirl, one of these character isn’t as attractive as the next because we know more about her than the fact that she’s a pretty face and a minx in bed.

Anderson also makes Rollergirl much more youthful and radiant in her appearance and energy than Maggie; we see Maggie frequently look pretty disheveled and hasty, especially in the more climactic scenes of the film where she is worried about getting her kids and her addiction to cocaine worsens. Both could have equal talent, but because we know about Maggie’s personal life, she is not portrayed as beautiful nor as radiant as Rollergirl, who always seems to be boasting a low-cut outfit that beautifully accentuates her features.

Ultimately, however, Boogie Nights heavily reflects feminist film writer Laura Mulvey’s ideas about the penis, castration, voyeurism, and scopophilia. In many ways, this is a film about power revolving around the penis; Laura Mulvey’s idea of “phallocentrism” – the idea that power comes solely from the penis and the possession of the penis – is highly prevalent here. Jack Horner is constantly seen as a powerful and dominant figure; a filthy rich but questionably moral individual that has made countless dollars peddling smut and never seeming to be the least bit preoccupied with the effects his business has on his performers or his audience. He has all the power because he is a suave talker, a ladies man, and, above all in Mulvey’s mind, possesses the penis.

Consider the aforementioned scene where Dirk Diggler and Maggie are about to have sex; nearly everyone on the set, be it the lighters, the camera operators, or the uninvolved bystanders, are males. Maggie is surrounded by an onslaught of men who are observing her and encouraging her to be a passive recipient of the penis – a direct and almost too literal iteration of Mulvey’s conception of power. Jack, at the center of it all, possesses the power here for more reasons than just his successful and lucrative business ventures.

But Jack, much like Dirk Diggler, has a serious fear of his power being corrupted or tarnished in any way. His uncommonly large penis is the reason for his success and he’ll be damned if anything comes to corrupt that. Though we do not see Dirk’s penis until the very end of the film, throughout the film, it is almost established like another character. Robert C. Sickels, who wrote a piece on the film, makes note of Eddie’s penis being a significant presence throughout the film by recalling the opening scene. He writes, “Shortly after Eddie meets Horner, Jack smiles at him and purrs, “I got a feeling that behind those jeans is something wonderful just waiting to get out,” thus establishing the presence of one of the more intriguing off-screen spaces in recent memory” (Sickels 52). This scene belongs to the opening sequences of the film, and establishes Eddie’s penis, though it’s unseen by Horner at this time, as something truly wonderful and worthy of a lot of recognition and power.

Sickels follows up the notion by commenting on the aforementioned scene between Maggie and Dirk, which works to establish the captivations and awe-inspiring attraction his penis draws. Sickels says, “Although it’s not seen by Anderson’s audience, the strength of its presence is conveyed in the reactions on the faces of all present on the set” (Sickels 53). With that scene, Dirk’s penis becomes an uncommonly worshipped and vital accessory of power and stabilization in an industry that will compensate him fruitfully if he chooses to use it wisely (or for as long as he can).

Be it the fact that female porn stars are often the ones headlined with the films they make, Dirk’s fear of “losing his power” (not being able to perform) or having the power and attention stripped away from him by younger starlets relates to the idea of castration on part of Mulvey’s theory. Castration works in the sense of a woman taking power (the penis) from a man. Boogie Nights emphasizes this through Dirk’s constant struggle to remain relevant during the excess period of the 1980’s, when porn becomes more acceptable, more risks and subversive routes can be taken, and older stars are left in the dust for the next generation of gorgeous bodies. Through these tough times, which even have Horner becoming more irritable and less welcoming of criticism on his old, traditionalist ways of filming pornography, Dirk becomes almost paranoid and self-conscious about not losing his commanding screen presences and the name he’s built from himself, but having it taken from him in the blink of an eye by someone, most likely a woman.

The paradoxical element is, despite this subtle but noticeable fear of being “castrated” or stripped of power, the ultimate loss of power Dirk eventually experiences is caused by his own body. One of the film’s most tender and dramatic scenes comes when Dirk, who has gone from an A-list porn star to a dime-a-dozen fling for horny men, cannot effectively masturbate in front of a complete stranger because of his inability to be erect. Though it conflicts with Mulvey’s ideas, this scene reflects the moment when power fails man and when man must learn to cope with the loss of power, which was possessed a moment ago, but is now gone with the wind.

Furthermore, Mulvey’s ideas of scopophilia and voyeurism play into the film’s style as well. The camera, which Mulvey argues has a default masculine perspective, of pornography inherently has an element of voyeurism involved because we, the audience, are watching an act between two people that is usually performed in private. Anderson recognizes this and, as a result, takes a step back to plunge us deeper into the idea of being a voyeur by seeing the sex these characters have in addition to the lives that they lead – arguably the most private of all. This element of voyeurism subverts the conventional idea of what being a voyeur in porn really means.

With that, the element of scopophilia – the pleasure of looking at other people as objects – as something that, as stated, is inherent to pornography and is recognized throughout the whole film when we have to focus on any kind of sex scene, whether it’s between Dirk and Amber or Rollergirl and a complete and total stranger her and Horner meet five minutes before both parties have their clothes off. While this aspect is readily apparent, Anderson is still more concerned with making us a voyeur into the private lives of these individuals more-so than objectifying them at every turn.

In an effort to really showcase the frequently examined ugliness of the pornography industry, Boogie Nights provides a fascinating look at the ideas of why porn stars are so attractive to us, male insecurity, power and castration, in addition to self-damning power, and voyeurism. The result is an alarming and clear distinction at where the line between erotic, theatrical pleasure and deeply troubled personal lives meet.

Works Cited

Sickels, Robert C. “1970s Disco Daze: Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights and the Last Golden Age of Irresponsibility.” 2002. Pg. 52 – 53. Book.

About Steve Pulaski

Steve Pulaski has been reviewing movies since 2009 for a barrage of different outlets. He graduated North Central College in 2018 and currently works as an on-air radio personality. He also hosts a weekly movie podcast called "Sleepless with Steve," dedicated to film and the film industry, on his YouTube channel. In addition to writing, he's a die-hard Chicago Bears fan and has two cats, appropriately named Siskel and Ebert!