Dune (1984) review

Dir. David Lynch

By: Steve Pulaski

Rating: ★★

Remembering David Lynch

Remembering David Lynch

1946 – 2025

1946 – 2025

This might come as as surprise to some faithful readers, but I went into David Lynch’s Dune practically crossing my fingers in hopes that I would like it and be one of the lone critical defenders of the macabre maestro’s maligned excursion into science-fiction. It was a futile attempt.

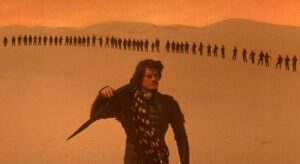

Dune is about as bad as you’ve heard: it’s bloated by a world it cannot sustain, with characters and relationships it can’t adequately develop, and a task too large for any lone film to be expected to accomplish successfully. Whether or not this film would’ve been 136 minutes long, like the theatrical version, extended to 177 minutes for the extended version, or 250+ minutes, it wouldn’t have mattered. Frank Herbert’s beloved franchise is among one of the densest works of science-fiction in the history of the genre, with over a dozen books spanning 15,000 years in a nonlinear chronology. The anomaly of making a successful Dune film is that, for one, it would require mapping out at least three as foundational films before experimenting with real conflict and quarrel in later installments. The cult-nature of the material suggests that contemporary budgets north of $150 million per film would not sit right with investors (we’d see several box office equivalents of Blade Runner 2049, in my opinion). I’ve long-held the belief that almost any property could be adapted into a good film; Dune is the first I’ve come across to challenge that very belief.

Lynch’s version was overseen by Italian producer Dino De Laurentiis, who purchased the rights for the material in the 1970s and commissioned several individuals, including Herbert himself, to write a script for an adaptation. When first and second drafts came became the equivalent of a three hour-long film, De Laurentiis poked around to try and urge Ridley Scott and Rudy Wurlitzer to come aboard the project. Had it not been for a death in the family and an intensive time-frame for production that was trying to be condensed at all costs, Scott might’ve stayed and our version of Dune might’ve at least been prettier. Eventually, after De Laurentiis secured an extension on the rights (a sign of how long and perhaps hopeless this project was), Lynch was hired, despite him having no knowledge of the source material nor any prior plan to make a science-fiction film.

What transpired was a messy, dispiriting relationship between Universal and Lynch that saw disagreements over the runtime to the point where his final cut privileges were turned over and the studio shrunk Lynch’s three hour film into a 136 minute one. Narration was added and scenes were truncated in order to compensate for scrapped footage. To this date, it’s a sore-spot for Lynch, who at least was able to followup this big bowl of wrong with Blue Velvet, arguably his best work. An extended cut has been released and runs a couple minutes shy of three hours, but it’s not directed by Lynch, but rather, the famous pseudonym “Alan Smithee.” How bad must the extended cut be if Lynch couldn’t even bear to have his name on it?

For me to describe even the essence of Dune‘s plot would be an unmitigated disaster, so boiling it down to the essence of its essence will need to suffice. It takes place in the distant future, where the universe is ruled by Padishah Emperor Shaddam IV, and the most important resource is the drug melange, colloquially referred to as “the spice.” The spice’s special powers include extending life and expanding consciousness, and the only planet that houses it is a dry, sandy one deep in the galaxy where not a drop of water exists. But perhaps the most valuable property of the spice is its ability to “fold” space, which allows for instantaneous travel.

We primarily focus on the House Atreides, a noble family with the young Paul Atreides (frequent Lynch collaborator Kyle MacLachlan) at the center. While trying to obtain the spice, he entangles himself in a web of relationships with grotesque-looking villains, all out to obtain the spice for personal gain. One whom is Baron Vladimir Harkonnen (Kenneth McMillan), a repulsive, boil-faced demagogue who hatches a plan with his nephews to infiltrate Atreides from the inside with the help of a mole. Paul uses his psychic abilities to save Atreides and to secure spice so that its properties do not become of service to those with bad intentions.

It’s abundantly clear by the hour-mark that Lynch has no idea how to adapt Herbert’s massive world into a digestible film under the given constraints. His lack of familiarity with the source material is clear, and his discomfort results in a narrative with staccato sequences that feel out of place or lacking in cohesion. The visuals are interesting enough; sometimes the feel like an episode of Star Trek: The Original Series in a campy way, but this becomes a deterrent if you consider that the effects artists were probably hoping their work with inspire more than comparisons of a TV show that wears its datedness with every episode. Characters have inky, ocean-blue eyes that look like someone toyed around with effects on an early model Macintosh, and scenes of space-folding have a lot of visual intrigue to them that works nicely along with the warping sound-effects employed for added immersion. These aren’t criticisms but simple statements on the quality and look of the effects. Quite frequently, they’re the most interesting elements on the screen. Lynch has always been a man consumed with the look of his films and how that breeds tones, but here it feels like a mask for a script he knows is not his prized work by any means.

Lynch’s script is a mix of intelligent and dopey. At times, characters expound upon the external effects of their actions in a manner that leaves you really curious about the impact their decisions might have. Other times, a character will say such actions might lead to a “genocide” and then proceed to define the word for us. Lynch has been a man fearless enough to take his own nonlinear, sometimes controversial ideas and adapt them into a film he can twist and turn to his liking, with no obligation to source material. When he needs to work off of preexisting material, like he did with The Elephant Man, the property usually allows him creative range to further emphasize his style. Dune doesn’t offer that same kind of leverage, at least for a man so committed to making things his own. It’s a limitless and particular world; the original novel came with a glossary of terms, making it one of the early science-fiction series to go the distance to implement its own language. All of this is set up for Lynch, but so much exists to the point where he tries to include it all, and unfortunately succumbs to biting off more than he can chew in material he was never cut out to develop.

The film was filmed on 16 different soundstages with a crew of over 1700 men and women, tirelessly conceiving a film I’m sure desperately few of them could explain. Intermittent beauty and effects aside, it’s a largely incomprehensible film swollen with too many characters, too big of a universe to build and showcase in one film, and too big of a liability for any director that tries to make it a conventional three-act film in one installment. You can almost feel the begrudging tension between Lynch and Universal while watching the film, and this is never a good trait to note in a film. Lynch is a master at his craft; something I can admit whether I like his films or not. With Dune, he misses and misses badly, craft aside.

In the present day, a Dune reboot is in the works with Denis Villeneuve set to direct. Villeneuve’s directed the aforementioned sequel to Blade Runner and made what many consider to be one of the best science-fiction epics of our time. He also directed the brilliantly thrilling Prisoners and the endlessly intriguing sci-fi film Arrival, which explored alien species using linguistics as a main point of interest. If Villeneuve can make even a mostly successful adaptation of one of the most “unadaptable” series known, he’ll go down in history as one of the best science-fiction directors ever. Maybe the best.

My review of The Grandmother (1970)

My review of Eraserhead

My review of The Elephant Man

My review of Blue Velvet

My review of Mulholland Drive

My review of Dune: Part One

My review of Dune: Part Two

Starring: Kyle MacLachlan, Kenneth McMillan, Brad Dourif, Richard Jordan, Freddie Jones, Linda Hunt, and José Ferrer. Directed by: David Lynch.

About Steve Pulaski

Steve Pulaski has been reviewing movies since 2009 for a barrage of different outlets. He graduated North Central College in 2018 and currently works as an on-air radio personality. He also hosts a weekly movie podcast called "Sleepless with Steve," dedicated to film and the film industry, on his YouTube channel. In addition to writing, he's a die-hard Chicago Bears fan and has two cats, appropriately named Siskel and Ebert!